When large corporations launch a new business initiative, i.e. a corporate venture, the first question is how to set up the team. Should it be in existing governance structures ('internal'), or separated in a special purpose structure outside of the existing governance ('external')?

Internal typically means that the executive who runs the business unit with the closest strategic interest is responsible for building the new venture. Often this means that a project organisation is set up with a temporary mix of full- and part-time resources from the business unit reporting to a steering committee.

External means separating the governance of the new venture from the core business, staffing it with specifically hired resources and setting it up in a different location. This also means that the core business executive is not fully in control. The venture team typically reports to the executive board, the CDO or the CEO. And most importantly, it doesn't impact the business unit’s P&L.

Why is the discussion internal vs. external so important?

Let's take an example: many supermarket chains are getting more serious about online grocery as a result of the Covid-19 crisis. Most of them have been running online grocery operations for years, but these are often mere extensions of their offline business and lack significance — in most European markets, online grocery penetration has been stalling around 1-2% market share. These have been launched with an internal setup.

Startups in this field such as GoPuff, the super fast delivery service of daily essentials with micro-fulfilment centres, or Picnic, the milkman-style neighbourhood delivery service, show that much steeper growth curves can be achieved. However, a very different operational setup is needed.

Both startups chose a completely new way of delivering groceries — an important area of the overall customer experience, which most incumbents completely neglected or outsourced to standard delivery subcontractors. It is not considered their 'core competence'. Also, revamping deliveries would require a completely new design of incumbents’ supply chain beyond regional distribution centres. A startup, however, starts with the customers' needs and then is uncompromisingly set up in order to fulfil these needs in the best possible way. They are not tied to old structures.

Supermarkets have set up online grocery operations as internal ventures but has this left them too tied to old structures?

If a supermarket chain intends to start one of these models and chooses an internal setup, can the team really tailor the operational design to customers' needs? Can they, for example, sell products the supermarket chain doesn't sell? Can they choose a significantly different delivery system, which would have an impact on the whole supply chain design? Are they even allowed to operate in specific regions, when the supermarket chain is divided into geographically separated business units?

You don't have to be a retail expert to see the unfavourable decisions that an executive who is incentivised to protect the core business' P&L would take.

This is not only true for supermarket chains. We observe these kinds of dilemmas in all industries. To be fair, it is not easy for executives to decide which initiative requires an internal and which one an external setup.

The internal setup has a lot of benefits, e.g. clear executive sponsorship, synergies of using existing governance structures and resources, and — especially — control. So, there is a natural tendency for an internal setup. For many innovation initiatives, it does the trick.

So, how do you decide?

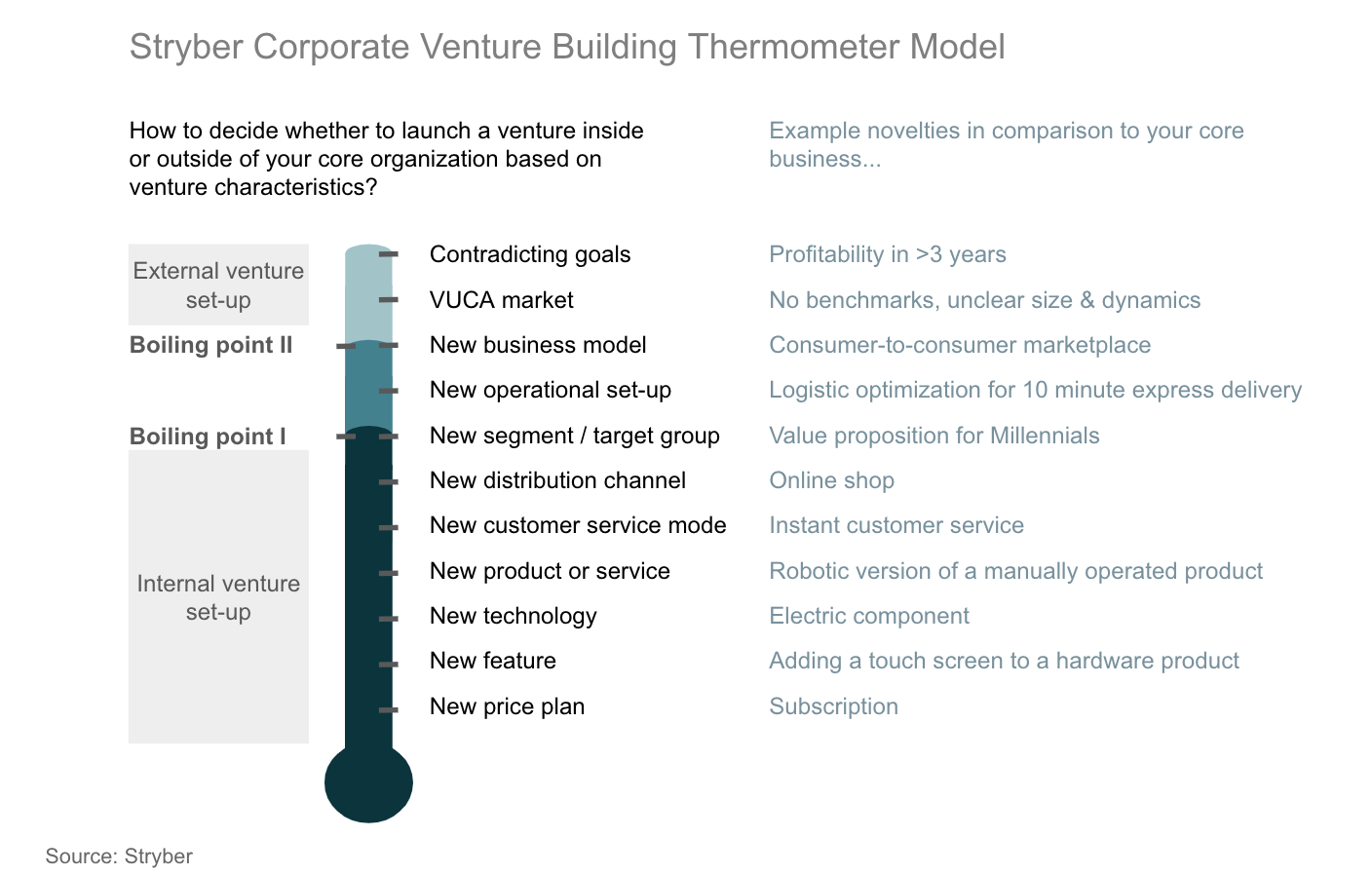

We’ve developed what we call the Stryber Corporate Venture Thermometer Model to help clarify things. It is an easy-to-use model that defines two ‘boiling points’: the first boiling point defines up to which point an initiative should run internally, and the second boiling point defines from which point an initiative should run externally.

In between, there is some room for corporation-specific judgement calls. However, from our experience, once a corporate venture is based on a new business model, is targeting an unclear, non-linear market and requires a goal set, which is incompatible with the existing KPIs for strategic projects, the governance of a corporation or a business unit is simply incapable of managing the specific venture.