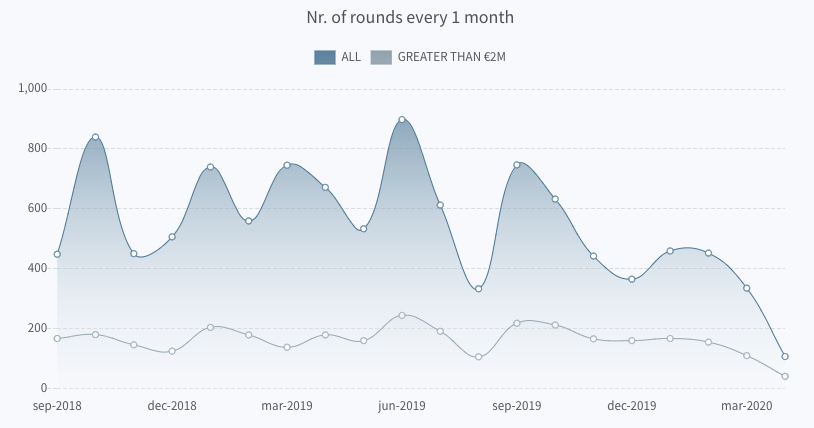

Venture capital investment in Europe is slowing down — but it hasn’t stopped. In March, €2bn was raised by European startups, and there were 108 rounds above €2m, according to data analyst Dealroom; around a 33% drop in activity from January. April is looking likely to be even slower — yet hundreds of term sheets are still going out, companies are still raising rounds (some big ones) and investors are still on the lookout for appetising investments.

However, many of those March deals were in the works pre-crisis — and didn’t pan out quite as originally anticipated. Valuations are dropping, some investors have been getting cold feet while other rounds have been closing faster than ever in a bid to just get deals done, and some term sheets have been renegotiated.

To understand what coronavirus means for startup fundraising in the longer term, the next three months will be far more revealing. “Year-on-year Q2 numbers are going to tell a different tale to year-on-year Q1 numbers,” says Daniel Glazer, partner at Wilson Sonsini, a law firm that works with US and European tech companies.

“A market-standard April 2020 term sheet is not the same as a November 2019 term sheet,” adds Glazer. “There’s a spectrum of what’s reasonable, and we’ve unsurprisingly gone from the founder-friendly side of that spectrum to the investor-friendly side.”

Let’s take a closer look at what’s happening now — and might happen next.

Valuations

Valuations are down — but it’s hard to say just how much. Estimates range from 10-40%, depending on the stage of the company, and most agree that later-stage startups will get hit the hardest.

The late Series A, B, C market is going down 30-50% because the market was way too high.

“The late Series A, B, C market is going down 30-50% because the market was way too high. Those companies were overvalued,” says Jean de La Rochebrochard, an early-stage investor at French VC firm Kima Ventures. “Pre-seed, seed, Series A, not much has changed.”

Investors may, however, try to get more equity for their money, he adds. “If you’re raising €500,000 to €5m, [you were going to give away] 20% of your company; now it might be 25% rather than 20%.”

Anthony Rose, chief executive of legaltech company SeedLegals, says that the median valuation of the angel and seed rounds closed via its platform are “completely unchanged”. Glazer at Wilson Sonsini, meanwhile, is hearing from companies and funds that valuations are dropping by 15-20%.

Entrepreneur First cofounder Matt Clifford told Protocol that he thinks companies at all stages will see valuation chops: “I expect valuations to fall 30% to 40%, even in seed, and at least that farther up the chain.”

“Valuations are down and companies are raising less money,” says Eamonn Carey, London managing director at early-stage investor Techstars. “Depending on the stage, it's anything from 10% to 30%.”

Pace and size of rounds

In the UK, data company Beauhurst saw a 30% decrease in the number of deals in the UK over the first three months of the year (compared to the last three months of 2019). For Europe as a whole, Dealroom is recording a notable drop in activity.

But some say March has felt very busy.

“In the last three weeks we have closed nearly 30 deals; in the same period last year, it was more or less the same,” says Shawn Atkinson, corporate partner at tech law firm Orrick. “We have been very busy — and we’re seeing an uptick in certain types of deal activity — i.e. clients calling with transactions they may not have otherwise done, such as further convertible notes or smaller inside rounds.”

To avoid raising money at a lower valuation than their previous round due to current market conditions, some startups are opting to take convertible notes — a form of short-term debt that converts into equity, usually at a future funding round — from existing investors, or raising “inside rounds” from them to avoid going out to market.

We're also seeing a lot of companies doing extension or bridge rounds at a flat valuation to their last round.

“We're also seeing a lot of companies doing extension or bridge rounds at a flat valuation to their last round — or maybe at a tiny premium — even ones that have had huge revenue increases,” says Carey at Techstars.

“It makes me think there's a massive opportunity for someone to get an interesting level of ownership in a lot of heavily de-risked companies by putting together a fund to invest in these bridge/extension rounds, ” he adds, pointing to the debate surrounding the proposed ‘Runway Fund’ to support struggling UK startups (find the arguments for and against on Sifted).

Despite having 800 portfolio companies to help out, Kima has been busy closing new deals — but de La Rochebrochard doesn’t fancy doing many more for a while. “We closed 15 new deals in the last two weeks; I’m tired of new deals. All the people we had engaged with in Q1 decided to close their rounds as fast as possible, and we got caught up in this. We had committed, so had to comply,” he says.

Not all investors are finishing off deals which were in the works pre-coronavirus, however, leading to a dip in the amount being raised by many companies. SeedLegals says the number of rounds on its platform is unchanged or growing — but it has seen 30% less being raised with 30% fewer investors.

“I think that with rounds that are beginning in this environment, there probably are somewhat fewer investors coming in. The rounds are becoming simplified. From a company standpoint, [there’s a desire to] pick your negotiating battles carefully and get the money in the door,” says Glazer.

Investors are also spending less time looking at completely new deals; many are either entirely stalling, or significantly dropping the time they spend on them.

“We were passing 20% of our time with our portfolio, and 80% of our time on new deals. Now we’re passing 80% of our time with our portfolio, and only 20% on deal flow,” says de La Rochebrochard. “Entrepreneurs are aware of that. All companies that can wait will wait. All companies that cannot wait will try to raise from current investors.”

Term sheet renegotiation

There have been instances of VCs behaving badly — but everyone Sifted has spoken to has stressed that these are few and far between. We’ve heard of investors backing out of deals just before closing and then refusing to communicate with the founder; others renegotiating the terms of deals done over a year ago; and valuations being slashed last-minute.

Some deals have been tougher to get over the line. Three people close to the £5m Series A fundraise of credit scoring startup Credit Kudos, which was announced last week, say that it looked rocky for a period with investors demanding a radically lower valuation. In the end, an accord everyone was reasonably happy with was reached.

SeedLegals’ Rose says that while any really bad behaviour will likely damage the reputation of investors in the long run, some readjustment should be expected.

Investment isn’t a charity. If circumstances change, I don’t see why investors can’t change their position.

“Investment isn’t a charity. If circumstances change, I don’t see why investors can’t change their position,” he says — so long as the term sheet hasn’t already been signed. “If you see investment as a long-term play, you probably wouldn’t do that.”

“I don't have first-hand knowledge of term sheets getting pulled,” says Glazer, but certain categories of investors more exposed to the plummeting public markets are getting cold feet. “We’ve seen strategic [investors] and angels get more skittish — especially when you have strategics investing off balance sheet.”

“I haven't seen a lot [of term sheets] that have been renegotiated at the last minute yet,” says Techstars’ Carey. ”There have been some valuation haircuts and some where people have ended up raising less than they anticipated. I've seen term sheets wither on the vine, and I've seen a lot of folks pull out of deals for a wide range of good and bad reasons.”

Some investors have pulled out of deals because they (or a member of their family) have the virus, others because they've lost money. "We've had a lot of folks who've become effectively or technically insolvent overnight," says Carey. "Some have just dropped out because they're anxious, and some have tried to renegotiate terms (not many thankfully) and then pulled out when they couldn't."

‘Investor-friendly’ terms

For a while, founders have been on a strong footing: strong startups have been able to set the terms. That has now changed — and the power is with the investors.

That means some ‘investor-friendly’ terms are edging into term sheets.

All the bad things we had managed to get rid of are coming back from investors who felt frustrated.

“All the investors who regret having lost power over the past years, because the market has been in favour of entrepreneurs, all those people jump on the opportunity to act like Robespierre,” says de La Rochebrochard. “Liquidity and participating preferences, ratchets, tranching of investments… all the bad things we had managed to get rid of are coming back from investors who felt frustrated.”

Europe’s most-respected VC firms won’t be acting like this, but the long-tail of less-established investors might be tempted to, he adds: “In venture you can lose money only once, and make it 100 times. If you’re playing the game of 2-3x returns and come with cheeky terms, that allows you to do 2-3x on each and every deal. If you’re playing the game of 100x returns, you don’t care about ratcheting and preferential shares.”

The use of these terms doesn’t seem to be widespread, however. “I haven't noticed anything really awful in the signed, executed term sheets that I've seen come across my desk since all this started,” says Techstars’ Carey. “No participating preferences, ratchets or anything else. I have seen people ask for anti-dilution provisions that are over and above the norm, and there are a few folks asking for warrants.”

Let’s remind ourselves of what those ‘investor-friendly’ terms are:

- Participating preference shares: “On a sale of the company, the investor gets their investment back first. Then the remaining proceeds are divided amongst all the shareholders (including the investor who already got their money back) proportional to the number of shares held,” explains SeedLegal’s Rose.

- “This ‘double dipping’ by investors (they get their money back first, then get part of the remainder) has largely fallen out of fashion — the world has moved on from the bad old days — and these days most times that investors get preference shares they’re non-participating, which means the investor can choose to get their money back, or a share of the proceeds, but not both.

- "In the UK preference shares are less common than elsewhere in the world because angel investors looking for SEIS/EIS tax breaks on their investment are limited to getting ordinary shares, though astute investors know they’re able to get a liquidation preference.”

- Liquidation multiples: “On a sale of the company, investors with preference shares get their money back before other investors. But, sometimes the investor might negotiate at term sheet stage a 1.5x or 2x (or even more) liquidation multiple, which means that they don’t just get their money back (a 1x multiple), they get 1.5x or 2x their money back.

- "Preference shares can mean that founders get little or even nothing on a sale of the company. For example, if a company raises £10m with the investors getting preference shares, and one day sells for £10m, the founders will get nothing, even though they may own 80% of the shares.”

- Anti-dilution provisions: “If an investor believes a company is raising money at too high a valuation, but they still want in, they may ask for anti-dilution provisions. This means that if the company can’t achieve the growth that it’s promised and has to raise the next round at a lower valuation (a “down round”) the investor has their shares topped-up, so that it’s as if their last investment was at the lower valuation, or somewhere in between.

- "Anti-dilution is sometimes confused with non-dilution, the difference is explained here.”

- Ratchets: “When an investor gets anti-dilution protection, there are various methods of calculating how much they should be topped up by. The most aggressive is the Full Ratchet, which can significantly dilute the founders on a down round. The more commonly used methods are Broad-Based or Narrow-Based Weighted Average, where the investor is topped up to some middle ground between the old and new valuation.

- "If a company’s valuation continues to increase at each funding round, anti-dilution won’t affect the founders. But in distressed times, like now, where a company has to do a down round, if the founders had given the investors a full-ratchet anti-dilution provision, they could be significantly diluted.”

- Warrants: “A warrant (in the context of a startup) is typically the right to buy a fixed number or shares, or fixed percent equity in a company, at a future time, for an amount of money that is agreed now. A common use case is an accelerator taking a warrant in a company that says, in return for our providing, say, £50,000 in services, we will get 10% equity in the company at the time of your next funding round.”

(And for an even more detailed look at terms to watch out for, see this piece from VC Fred Destin.)

What next?

Some companies will, inevitably, have to raise money over the next six months. April to June is likely to be quiet, as investors continue to focus on helping their portfolio and take stock of where the world is heading. July to September might also see little activity — and the run-up to Christmas could be busier than ever — but nobody really knows.

In the meantime, startups pitching to investors remotely “need to up their game on their pitch materials”, advises Glazer at Wilson Sonsini: “Those materials need to do a lot of the work for you; make them as easy and compelling as possible for potential investors.”

It’s also important not to stick your head in the sand, adds Glazer. “It’s important for companies going out fundraising now that they spend a little bit of time addressing the positives and negatives (if any) of the Covid-19 environment in their executive summary and pitch deck,” he says. “Some of the feedback I’ve heard from investors is that they don’t know whether the company has baked into its calculations the reality that April 2020 (and some period of time to come) is going to look different. If a company addresses that head on, our experience so far is that it reflects well on the company.”