The legal sector does not, at first glance, seem like a standard bearer for innovation.

The core business model and go-to market strategies of most corporate law firms have remained static for more than half a century. The practice of law is enshrined in history and precedent. The success of a firm is based, in large part, on the expertise of its people and the strength of relationships cultivated over many years by its most senior constituents.

Much of the heavy lifting in litigation, transactions and M&A deal rooms continues to be performed by legions of associates and junior staff — even if digitisation has given a modern veneer to the process.

But this is changing. Innovation, once seemingly unnecessary in a sector that just kept growing, is now widely recognised as essential to navigating a changing future — even if the partnership business structure disincentivises it, and some law firm bosses still resist it.

Sifted spoke to Ben Allgrove, partner and chief innovation officer at Baker McKenzie, a worldwide top-five law firm, to unpick what they’ve learnt on a journey to build innovation capability over the last five years.

A perfect storm

The corporate law firm of today is under threat.

On the face of it, these firms seem bulletproof — the quintessential cash cow. They win in good times and bad. They ride out recessions and crises. They even thrive during global pandemics. It’s said that the only certainty in life is death and taxes. A third, it seems, is high demand for legal services.

However, market forces and technological advances more familiar to other sectors have been catching up.

Today, incumbent corporate law firms are in the eye of a perfect storm, facing the convergence of three substantive forces. In isolation, any of these three would be enough to cause concern. In concert, they’re as much a threat as an opportunity — depending on how you respond. Either way, they’re creating the need for change.

Increasing price pressure

“We’re talking about a business model and a sector that’s been wildly successful for more than 50 years,” explains Allgrove. “You had law firms posting consecutive double-digit year-on-year growth, and all you had to do to fuel this was add more people. There was just a firehouse of work coming through, and in that environment, you don’t tend to see innovation.

Simply, the market said ‘we’re not willing to pay any more’

“But post-financial crisis [2007-08], and really starting to become acute around five or six years ago, price pressure became significant. Simply, the market said ‘we’re not willing to pay any more’, introducing caps [maximum fee limits] and demanding more creative and value-based approaches to pricing than the traditional (and cost-centric) billable hour.”

Rising cost and competition for talent

At the same time, costs have been rising.

“Just as clients are pushing back on fees and demanding greater value for their spend on legal services, we also see a war for talent. Starting salaries for junior lawyers have begun to skyrocket, initially in the US but now more broadly across the UK, Europe and Australasia.”

Vendor diversification and competitive disruption

For global firms, this dual top and bottom-line pressure is felt at scale and represents quite a crunch. But completing the trifecta is a disruptive competitive environment.

“The ‘big four’ [accounting and consulting firms] have taken another look at the legal sector,” Allgrove continues, “and with this they bring more resources, more people, more systems and more processes. Added to which, they also have access to the C-suite through the CFO, relationships which law firms typically lack.”

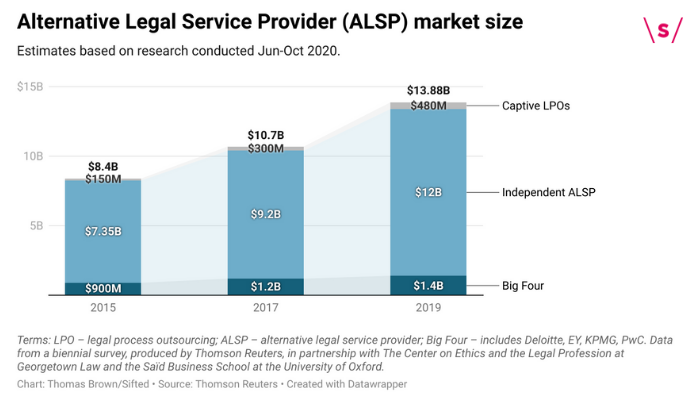

It’s not just the "big four" encroaching on "big law". Technology has long had its sight on the knowledge economy with law being no exception, and not just for low-level, low-value process automation. Investments in lawtech or legaltech startups are growing around the world, and the sector has also seen the emergence and growth of so-called alternative legal service providers (ALSPs), providing corporate clients with lower-cost, more efficient and technology-fuelled services such as ediscovery and document processing.

“Revenue pressure, margin pressure and vendor diversification,” says Allgrove. “Combined, this began a series of conversations about the need to change — and that’s sector-wide, not just within Baker McKenzie. Those conversations began to coalesce into a strategy, rather than a reactive response to what was happening in the market.

“And it’s then that we realised that our existing culture — one built on entrepreneurialism and becoming the go-to global firm — would need to evolve. We needed to ask how to tap into that entrepreneurial spirit and refashion it for an innovation, rather than geographic expansion, agenda.”

Allgrove recognised that leaders have to send a clear message: that change needs to happen, that it is happening, and that the people who control the levers in the business will be held accountable for their part in making it happen.

“This isn’t just about getting sign-off from the executive team,” he says. “It’s about the top-team setting the tone for the rest of the business.”

A reluctant innovator?

Allgrove concedes that when these conversations began among the firm’s leaders, "innovation" was seen as an unnecessary distraction and a waste of resources.

“If you’d have asked the partners, the majority would have said we should be spending our money on hiring the best lawyers and paying them well so that we can compete for talent in the market. That’s what we knew, and what had worked for several generations.”

I think the word ‘innovation’ is debased of most meaning these days, and actually counterproductive

In fact, while Allgrove has played a leadership role in the firm’s innovation strategy for more than five years, formally badged the global head of R&D, he only assumed the chief innovation officer title as recently as September this year.

“Throughout that time, I resisted the chief innovation officer title. And I resisted calling what we were doing an innovation strategy,” he explains. “The reality is I’ve relented because that’s where the market’s gone.

“But I do think the word ‘innovation’ is, to be frank, debased of most meaning these days, and actually counterproductive to most conversations. But it is what the market talks about.”

Building alignment — four critical ingredients

Overcoming this internal scepticism took more than a mandate from a visionary leader (which the firm was fortunate to have in its global chair at the outset of the journey, and to whom Allgrove credits with nurturing the seeds of the firm's innovation agenda). Reflecting on the last five years, he shares four key learnings with Sifted.

1/ The importance of (personal) conversations

“You’ve got to be willing to put the hard yards in and have the conversations with people. You can’t just broadcast a strategy and expect it to be adopted and bought into.”

You can’t just broadcast a strategy and expect it to be adopted

Every organisation has its true believers — the 10% that are signed up to new, creative ideas for the future and need almost no convincing.

“You’ve got them from the start,” Allgrove says. “But the majority of the partners and senior non-lawyer population required conversations about what our innovation agenda meant to them, why it was relevant and why they needed to know. This requires a lot of time, outreach and personalisation of the message.”

Grunt work, he says, is a core part of the job.

2/ Putting political capital on the line

Allgrove argues that, in the legal sector at least, having the innovation agenda led by a practising lawyer was “instrumental” to getting traction in the early days.

Having someone from the leadership willing to sacrifice 50% of their time adds credibility

“Having someone from the firm’s practice leadership willing to say ‘this is the future, we need to change and I believe in this’ is key. But having that person also say that they’re willing to lead that agenda, to sacrifice 50% of their time to serve as chief innovation officer rather than focus on business as usual, going out and selling work and growing their practice — that’s seen as a risk, but it also adds credibility.”

Allgrove calls into question whether an outside candidate without the same skin in the game would have been as successful. It might be tricky to ask people to take risks, make investments and make sacrifices when they wouldn’t share in doing so personally.

“In our business, if it wasn’t a partner, if it wasn’t somebody taking a risk with their practice, there would be a question as to whether everybody else should make the investments needed to make that shift.”

Keeping leaders engaged beyond initial buy-in efforts is a further challenge, and one which Allgrove has addressed with the Reinvent Board (Reinvent being the firm’s brand for its portfolio of innovation efforts). This board comprises 11 individuals plus Allgrove as chair, with the members being the holders of the firm’s main revenue streams.

“In the early days we had an innovation committee, but this wasn’t wholly successful,” Allgrove explains. “The idea behind the Reinvent Board is that when we’re setting innovation priorities across the business, whether that be in talent, technology, finance or the lawyer community, we have the most senior P&L [profit & loss] leaders in the business at the table, and we have a conversation about prioritisation and resources."

When they ask ‘who made that decision?’, the answer is ‘your representatives did.’ This changes the conversation and immediately builds confidence

Allgrove believes that this group's mirroring of the commercial structure of the organisation, and putting these individuals in a formal governance role, helps avoid ambiguity or inaction.

“When someone says ‘we need to do X’ and the wider group agrees, we then turn immediately to the questions of who will be accountable, who will deliver it, how we will resource it, and where the budget will come from."

In addition to helping make things happen, Allgrove says the Reinvent Board structure also gives legitimacy to innovation investments in the eyes of the partners.

“When they ask ‘who made that decision?’ regarding innovation, the answer is ‘your representatives did… the people that you elected into those major P&L roles on your behalf.’ This changes the conversation, and immediately builds confidence.”

3/ Targeting below the top team

While a firm believer in the "it starts at the top" mantra, Allgrove cautions against focusing exclusively on the top team, suggesting that innovation leaders need to extend their alignment efforts further into an organisation.

“There are certain key influencers and decision-makers in the business, both within the lawyer community but also across technology, talent, operations and finance teams, that had to buy in to the strategy.”

“At the end of the day,” he continues, “I can talk strategy, I can shout from the rooftops ‘this is what we should be doing’… but they’re the ones implementing.”

I can talk strategy, I can shout from the rooftops ‘this is what we should be doing’… but they’re the ones implementing

In an organisation of Baker McKenzie’s size, this couldn’t be the purview of a single individual. A bottom-up approach was pursued, involving building a global network of ambassadors across all functions and professions within Baker McKenzie, which has now reached a significant scale and serves as far more than an internal communications channel.

“We wanted to identify and inspire a community of people who are interested in innovation in our practice, providing fora for them to communicate, share, learn and interact.

“We now have more than 1,200 of these ambassadors across the business. These are the people we pull into projects, be they part of our transformation efforts or live projects for clients. And they’re the people who are out talking to practices and teams to bring the innovation strategy and the firm’s priorities to life.”

4/ Communicating the unsexy

Allgrove acknowledges his final learning is more of a work-in-progress than a case study candidate.

People, quite fairly, pointed to gaps in some of our basic systems and processes, asking whether we were trying to run before we could walk

“I get the question on an almost daily basis — what has the innovation strategy actually delivered?” he explains. “The reality is that lots of the stuff we’ve done wouldn’t have happened but for the innovation strategy pushing it along, particularly around our technology infrastructure and data structure to enable machine learning.”

These examples are unsexy but mission-critical investments, as Allgrove describes, and leaving them below the radar, or failing to explain how they lay the groundwork for more exciting future innovations risks harming the internal narrative.

Beware the quick wins

Allgrove is a believer in making strategy real swiftly, with some quick wins to help keep people bought in. But he also offers a word of caution.

“In the early days we tried to please everyone,” he says. “In reality, it was hard to do things that people across the business could touch and feel, and that ticked a box for everyone. We decided to stop doing that, to be honest, because we didn’t have the infrastructure in place, or the resourcing, to deliver what people needed.

“People, quite fairly, pointed to gaps in some of our basic systems and processes, asking whether we were trying to run before we could walk. And some of those criticisms were fair.”

Allgrove says that his team stopped and recalibrated. Asked themselves what foundational infrastructure they needed in place to enable their innovation strategy over the medium-to-long term, covering areas such as cloud, technology platforms, data and applications.

“We communicated our strategy to our tech team, told them where we were headed and what capabilities we needed in five or six years’ time. We told them to start getting plans and budget requests in now, to get us to that point in time. And that approach — empowering our people to invest for a long-term that they more fully understand — has been wildly successful for us.”

TL;DR? Key takeaways…

- You can’t just broadcast strategy and expect adoption — you’ve got to put the hard yards in and have the conversations;

- Putting your own political capital on the line adds credibility;

- Don’t create new committees for the sake of it — align with, and embed with, where the power and the money lies in your organisation;

- Decision-makers exist below the top team — overlook them at your peril. Harness people across the organisation with their own expertise, networks and circles of influence;

- You’ve got to communicate the unsexy stuff, too;

- Beware the quick wins — you’ll never find things to please everyone, and you might find you’re trying to run before you can walk;

Share your perspective

We’d love to hear from you…

🤔 What most resonates from Ben’s learnings and advice?

🤷🏻♂️ Do you think the term innovation might be working against you?

Share your thoughts and ideas in the comments below, or on LinkedIn or Twitter using the hashtag #FutureProofonCulture.

Thomas Brown is Sifted’s corporate innovation reporter, and a freelance journalist, award-winning author and consultant, specialising in digital transformation, innovation, organisational culture and consumer behaviour. You’ll find him tweeting from @ThinkStuff.

Ben Allgrove is a partner at Baker McKenzie, with a dual role as a technology and media lawyer and chair of its Global IP & Technology Group, as well as serving as the firm’s chief innovation officer. Originally qualifying in Australia and working as an associate in both the South Australian Supreme Court and to the then Solicitor-General of South Australia, he joined the firm in 2004 after attending Oxford University where he was awarded a BCL and MPhil (Law), both with distinction.