Aviv Wolff has a pretty chunky ambition: cut out animals from the human food chain.

"We want to eliminate the need for animals in our food system in order to save resources, land and reduce emissions," says Wolff, who is CEO and founder of Remilk, an Israeli startup leading on precision fermentation.

And he’s not alone in that goal. Companies across Europe are racing to create the first imitation of dairy proteins, without the involvement of cows, using a technology called precision fermentation. They hope to replicate the specific fats and proteins that give milk and cheese its distinctive flavour and texture so consumers can switch to cow-free dairy products not because they feel guilty, but because they’re so delicious.

Investors are also betting big on animal-free cheese and other dairy products as demand soars. A record $5bn was invested in alternative proteins in 2021, and the precision fermentation market is estimated to be valued at $1.6bn in 2022. By 2035, the market for alternative proteins could account for as much as $290bn, or 11% of the global protein market.

But companies face major regulatory and financial hurdles along the way as they try to compete with the heavily subsidised dairy industry and make non-animal cheese, milk and yoghurt mainstream.

Scaling up

Precision fermentation uses microorganisms to reproduce casein and other functional dairy proteins by combining fermentation processes with biotechnology. Companies like Remilk use DNA splicing to introduce genes into yeast microbes, allowing them to replicate proteins that are identical to those found in traditional dairy which producers can turn into cheese, yoghurt and milk alternatives.

"One of the advantages of precision fermentation, compared to animal farming, is that it's extremely scaleable," says Wolff. This is because the technology can produce large amounts of alternative proteins — by placing yeast encoded with a milk protein gene into a bioreactor — and doesn’t involve any of the external resources, such as land, feed and water, needed to rear cows.

But there are still challenges when it comes to scaling up precision fermentation technology, says Raffael Wohlgensinger, CEO and founder of Formo, a German startup that aims to replace 10% of Europe's dairy with lab-grown products by 2030, or "roughly equivalent to Nestlé's total dairy business”.

"A lot of the processes and technologies we're using traditionally come out of the biotech and pharma industries, so they're developed for small-scale, high margin products, such as antibiotics," he says. "But we're doing this for bulk ingredients and producing food at high volumes which requires another step in innovation."

"To meet the demand for these alternative products, we need to add 30m-60m tonnes of global annual bioreactor [the steel tanks that foods, cosmetics and medicines are increasingly produced in] capacity, more than a doubling from today’s level," says Nate Crosser, a principal at VC firm Blue Horizon.

As tasty as the real thing

Another challenge ahead for alt-cheese startups: making their products tasty.

Plant-based alt-cheese — which is often made from soy and nuts — doesn’t cut the mustard, says Wohlgensinger, and so it’s not meeting the huge consumer demand out there. "I've been a vegan for eight years. I want to eat cheese again but the plant-based alternatives aren't good enough."

Formo, which raised $50m in a Series A funding round last year from EQT Ventures and Lower Carbon Capital — one of the largest funding rounds in European food tech — is collaborating with artisanal cheesemakers and chefs to ensure that they get the starter cultures, the moulding and taste profiles exactly right. By combining this knowledge with biotechnology, they are creating casein and other functional dairy proteins that can replicate the taste and texture of real cheese.

"The majority of cheese lovers around the world won't switch [to a dairy alternative] unless there is a product they are 100% satisfied with," says Wohlgensinger. "Changing habits is super hard."

Remilk says products made using its proteins are indistinguishable in taste and texture from animal dairy. In trials, “no one can tell the difference between our ice cream or cream cheese and the traditional products," says Wolff.

UK startup Better Dairy, which has raised almost $27m to date from investors including Redalpine and Happiness Capital, believes precision fermentation could even produce healthier, tastier and more sustainable cheese than the "real" thing.

"When you look at the flavours and textures, you have an element of control that no dairy farmer or manufacturer has ever had before," says Better Dairy cofounder and CEO Jevan Nagarajah. "It means that we can rid the product of lactose and hormones which can cause people to break out and are just inherently [found in dairy] due to animals being involved in the process."

Regulation challenges

Formo plans to launch its cheeses in Singapore next year, followed by the US and finally Europe. The EU market is harder to crack as companies producing lab-based dairy must receive approval from the European Food Safety Authority, via their novel foods pathway. They have to be able to guarantee food safety and consumer rights, while also adhering to non-discrimination rules.

"It just takes longer," says Wohlgensinger. "But we are a European company and we perceive Europe as the key growth market."

Remilk, which has raised around $160m from investors including Hanaco Ventures, Precision Capital and CPT Capital, is focusing on the US and Israeli markets. The company recently signed an agreement with Tara Dairy, Israel's second largest milk producer, to start developing animal-free dairy products using Remilk’s technology. Remilk proteins have also been approved as safe by the FDA, allowing the company to sell them for consumption in the US — although it doesn’t yet have any announced partnerships with food producers.

“Requiring novel foods approval is a slow and quite expensive process,” says Robert Lawson, managing partner at Food Strategy Associates, a strategy consultancy for the food industry.

But he doesn’t think it’s a killer for the industry. "In my view regulatory issues are a management challenge today but can be overcome.”

Reaching price parity

"The bigger challenge is an economic one,” adds Lawson. “Precision fermentation can be very capital intensive — if the molecule being created is complex then the processes work more slowly.”

“The challenge is whether more complex proteins can ever be manufactured in a cost-effective way such that the technology can be commercially viable,” he says.

Wolff says Remilk aims to reach cost parity by focusing on producing “an ultra-efficient microbe strain” and a “highly efficient conversion of inputs to outputs”.

“Think about the amount of resources (the land, water and feed) and the amount of energy that you need to put into a cow in order to get the milk,” he says. The single-cell microorganisms that Remilk works with don’t need all these valuable external resources to grow and produce milk proteins. “We can produce the same proteins cows are making, just faster, cleaner, with no animals harmed and only a tiny fraction of land and valuable resources,” Wolff says.

“Currently the limiting factor is production capacity,” he adds.

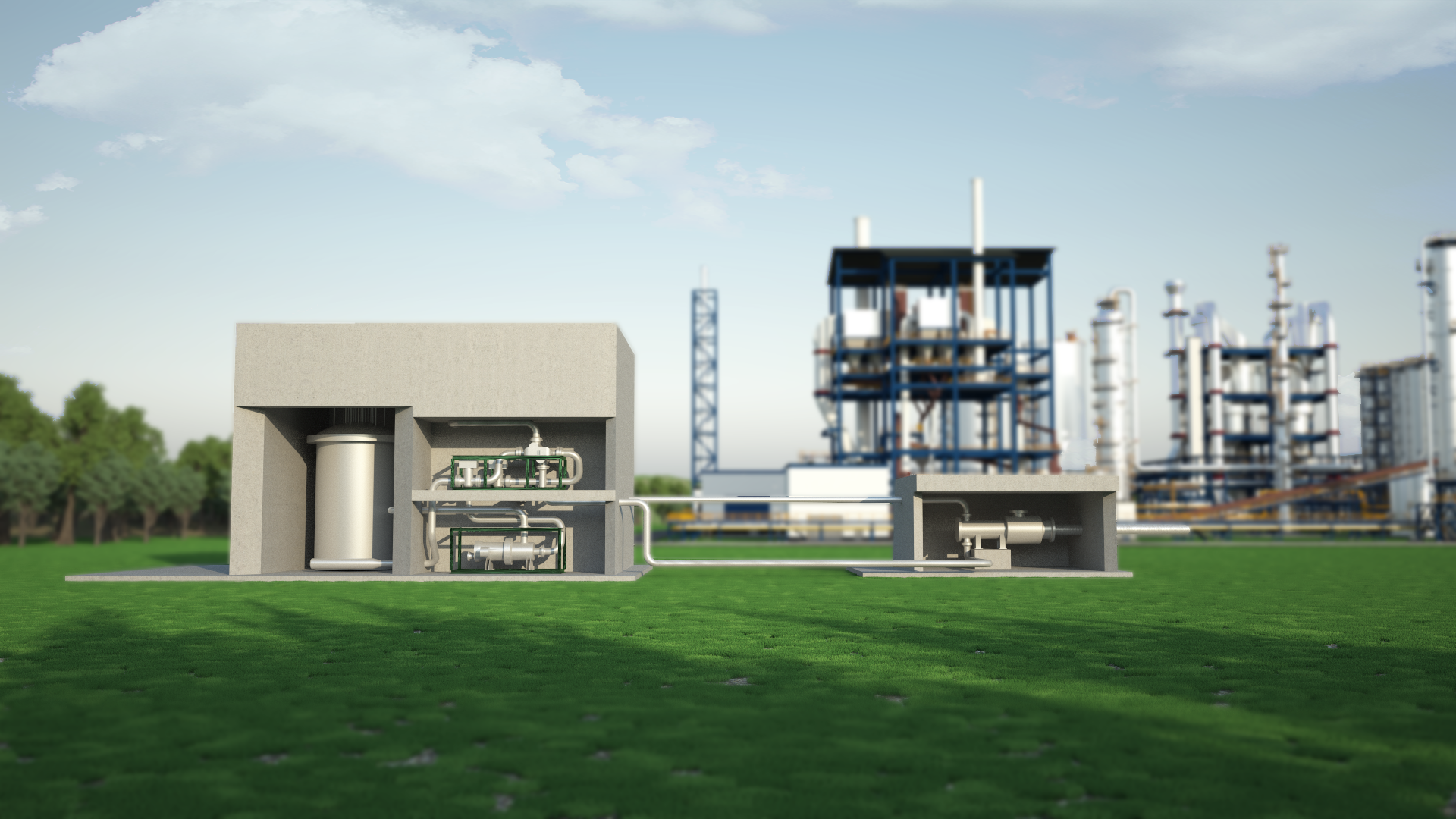

To get around that, Remilk is building the world's largest precision fermentation dairy factory in Denmark, following its $120m Series B funding round in January. The 750k sq ft facility will allow Remilk to reach cost parity from 2024 as it will enable the company “to maximise and optimise every piece of the production,” says Wolff.

It’s important for us first to own the story and educate consumers

Another challenge is competing with the traditional dairy industry which is heavily subsidised, especially in Europe, says Wohlgensinger: "There is a very strong dairy lobby in Europe." A dairy farm in France, for example, receives an average of €35k, or 20% of their annual turnover, from the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy, which pays out over €60bn per year to EU farmers.

“The focus of the first launch definitely is not profitability,” says Wohlgensinger. “It’s important for us first to own the story and educate consumers.” As the company scales and gets market access, Wohlgensinger is hopeful that it can offer alternatives at a competitive price from 2026.

“Over time, we should be able to get the price down even without the help of the government and the subsidies because this technology is far more central and efficient than traditional animal agriculture,” says Better Dairy’s Nagarajah.

He says there is room for many companies working on precision fermentation to coexist in the market. "The pie is so big. You could become a unicorn just off the back of creating a cheddar alternative for the UK market," he says.